How the AAU unjustly ended Jesse Owens’ career

By JOHN KEREZY, eyeonclevelalnd.com founder

Christmas Day 1936 found Jesse Owens in Havana, ready to run a 100-meter race against Julio McGrew. Owens had won four gold medals in Berlin at the Summer Olympics just months earlier, and at that time was the best-known and most admired athlete on planet Earth.

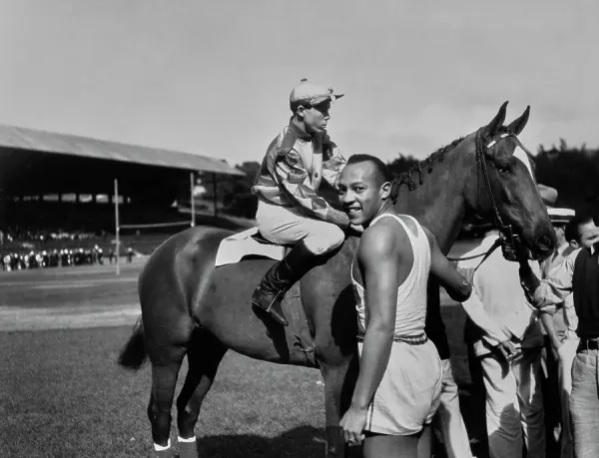

But on December 26, his opposition, McGrew, was a racehorse.

How did this happen? Why did the world’s fastest human, nicknamed the Buckeye Bullet when he ran track and field for Ohio State University, end up not being able to compete against other track athletes?

It was both a tragedy and a travesty, as the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) and one man – Avery Brundage of the (then named) American Olympic Committee — carried out a vendetta against Owens. Sadly, Brundage’s actions contributed to Owens entering a period of his life best described as “survivor mode,” finding it very difficult to get by as a husband, father, and a highly-respected athlete.

PROFITING OFF OF SUCCESS

To help raise money for their nation’s Olympic programs, it was a regular practice for athletes to barnstorm, compete in exhibition meets, after the Summer Olympics. Athletes from Europe, including some of Germany’s top runners, appeared in barnstorm meets while working their way eastward across the United States after the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Eventually they wound up in New York, where they bought passage back to Europe on ocean liners. The Olympic committee or athletic association of the countries they represented would receive a percentage of the ticket sales – gate receipts – from the meets.

On their way to Europe for the 1936 Summer Olympics aboard the ship SS Manhattan, AAU secretary-treasurer Daniel Ferris explained to the US Olympic Track & Field team there would be barnstorm meets in Europe after the Berlin Games were over. But details were quire vague: no specific dates and places were mentioned, and there were no contracts or even entry forms for the athletes.

Track and field was a huge spectator sport in Europe, and tens of thousands of fans would attend meets. The beneficiaries of U.S. barnstorm profits would be the American Olympic Committee and the AAU, which had an estimated $30,000 deficit leading up to the Olympic games. Then – as now – there would be a direct correlation between a country’s success in competition and public interest in seeing athletes compete afterwards.

WANT TO READ THE DIARY JESSE OWENS KEPT WHILE CROSSING THE ATLANTIC OCEAN IN 1936? Here it is:

In the Summer Olympic Games, US track and field competitors shined. Stars and Stripes athletes won a total of 25 medals, most of any nation. Black athletes earned 14 golds, led of course by Owens’ quartet of top prizes. Due to their success, American athletes were in high demand for post-Olympic barnstorming. So much so, in fact, that the AAU didn’t even wait for the Berlin Games to end.

The AAU signed contracts and began having its top track and field stars competing against national teams on their (Europe’s) own turf, beginning on August 10 – only one day after Owens ran the lead leg of the US’s winning 4-by-100-meter relay team in a world record time of 39.8 seconds. There was no time for rest in the Olympic Village for Team USA Track & Field’s members. There was money to be made from barnstorming for the AAU and the American Olympic Committee (AOC).

LIKE MERE CATTLE, SHIPPED ABOUT

Later on that same August 9, Owens and other track and field athletes traveled by land to reach Cologne, 360 miles away, where a crowd of 35,000 ticket-buyers watched U.S. track and field athletes compete. After the meet, Owens and other U.S. athletes attending a banquet in their honor which lasted past midnight. Early the next morning, Aug. 11, Owens embarked by plane to join another Olympian group (headed by miler Glenn Cunningham) in Prague for an exhibition against Czechoslovakian athletes. Owens was rushed from the airport to the stadium to make the 6 p.m. meet in time. He won the 100-meter race and the long jump, but his marks were nowhere near his Olympic records. He was exhausted.

The day following that, Owens, Cunningham, and all the Americans traveled by plane from Prague back into and across Germany to Bochum for another 6 p.m. meet. Owens matched his 10.3 second Olympic record there. Immediately after that competition, the U.S. team members boarded a night flight across the English Channel to London. They landed around midnight at Croyden Airport near Britain’s capital.

The AAU had options. It could pay the athletes a per diem allowance for meals. It could have even awarded them a small part of the proceeds as participation fees (more below). But instead, it often didn’t provide the athletes with food or even meal money.

The Brchum group ate stale sandwiches at Croyden airport and sat or slept on cots in an empty hangar until another plane from Hamburg arrived with more American athletes. Then the entire group checked into a London hotel and had two days of rest (August 13 and 14) prior to an exhibition against a combined British and Canadian team of track and field athletes.

Again, the AAU did not even feed the American team nor make any plans to care for team members while they awaited the exhibition. In a story a year later, Snyder used the words “trained seals” and “mere cattle being shipped about” to describe how the U.S. Olympic athletes were being treated at the time. While in London, the track stars mostly stayed in or near their hotel due to a lack of financial means. To a person, they were out of funds and thus didn’t engage in much sightseeing.

“Somebody’s making money somewhere,” Owens told a reporter. “They (implying the AAU) are trying to grab all they can, and we can’t even buy a souvenir of the trip.”

A year later, Owens, his coach Larry Snyder and others learned details of the financial contracts. The AAU was guaranteed 10 percent of the ticket receipts for the track meets, but it increased to 15 percent if Owens competed. Owens received nothing, and of course was never told about the arrangements.

DOLLARS DANGLED

The son of an Alabama sharecropper, Owens had two part-time jobs while he studied at Ohio State University. He also worked summers when he returned to Cleveland, which had become home for Owens when his family moved there in 1922 as part of the Great Migration. At times he sent money back to his parents to help make end meet, even while he and his wife Ruth were raising an infant daughter Gloria.

Now a world-renowned superstar athlete, suddenly big dollar signs were being dangled in front of Owens. He received a telegram while in Berlin which offered him $25,000 to appear on stage for two weeks with a California orchestra. Singer Eddie Cantor’s agent had proposed paying Owens $40,000 to appear with Cantor on stage and on radio broadcasts for 10 weeks. Al Jolson offered Owens $20,000 for a similar joint appearance arrangement. Owens had never even earned $1,000 in a single year before.

Snyder, incensed at how the AAU was treating Owens and others, arranged for the Buckeye Bullet to confer with Harvard’s athletic director, William Bingham; an NCAA Administrator, Alfred Masters; and Indiana University’s track coach, William Hayes, while all were in London. They agreed with Snyder’s assessment that the colleges were providing the AAU with athletes for the meets while leadership within the AAU and AOC were treating the competitors horribly.

This group’s consensus was that Owens should be free to determine his own future. Buoyed by this, Snyder rejected a representative of the Stockholm exhibition promoter who wanted to present him and Owens with plane tickets for the next scheduled barnstorm meet on August 16.

Owens and his teammates competed in a U.S versus Commonwealth nations track meet at White City Stadium in London on August 15, also the next-to-last day of Olympic competitions in Berlin. There was a throng of 90,000 fans in attendance. Owens raced in only one event, the 4 x 100 relay, running the third leg. He received the baton from Marty Glickman and handed off to anchor runner Ralph Metcalfe (see photo). The U.S. won the event, and also won the meet, 11-3.

From August 9 to August 15, Owens had traveled more than 1,100 miles and raced in one Olympic and then four different track exhibitions. He was broke. He’d lost 10 pounds too. But no one could have predicted that White City would also be Owens’s final track meet as an amateur.

SUSPENSION

Later that same night Snyder received a phone call from an angry Brundage of the AOC. Still in Berlin, Brundage had received reports that Owens had refused to fly to Stockholm. Brundage threatened Owens with suspension if he didn’t compete in Sweden. Snyder pointed out that Owens had not signed any entry or application forms to compete in this exhibition meet, and thus — by the AAU’s own rules — he could not be suspended for failure to meet a commitment.

The next morning Owens did not travel, instead remaining in London as he and Snyder prepared to sail back to the U.S. When the Stockholm exhibit committee heard Owens wasn’t coming, its chair called Ferris in Berlin to protest Owens’ “withdrawal” from the meet. Ferris immediately called London and spoke with Snyder. The conversation became heated as Ferris insisted that Owens should be on his way to Sweden. Snyder defended his superstar.

“Jesse’s got a big chance. He’s got a break that comes once in a lifetime and never comes at all to a lot of people,” Snyder said to Ferris. “…What kind of friend would I be to stand in his way?”

ARE YOU AN EDUCATOR?

Here are two Learning Guides based upon Jesse Owens’s life, triumphs, and tragedies. They were developed for high school classes. Click for details.

Snyder and Owens booked a voyage on the Queen Mary for a return trip to the U.S. But in Berlin, Brundage and Ferris retaliated. On the final day of the Olympics, August 16, Ferris announced that the AAU accused Owens of violating contractual commitments and suspended him indefinitely from competing in any track and field meets in the U.S. The two conveniently left out the fact that no such contract existed.

It was a travesty.

Back in the US, public and editorial opinions in the U.S. were solidly behind the Buckeye Bullet and against the AAU’s stance. Typical was an editorial in the Chicago Tribune, which read in part:

He (Owens) may have agreed at one time to join the junket, but he changed his mind. That is an amateur’s privilege. It is what distinguishes him from a professional. As he was to receive nothing for his appearance in Scandinavia, no contract binding him could have existed. Somebody should tell the moguls of amateurism about the Emancipation Proclamation.

Once back in the US, Owens eventually signed a contract with Broadway promoter Marty Forkins, best known as Bill “Bojangles” Robinson’s agent, who arranged multiple paid promotions for Owens. Sadly though, most of the telegrams Owens received while in Berlin and in London, dangling huge dollar signs at him, were phony.

But in reaction to Owens’ agreeing to promotional activities with Forkins, the AAU made its indefinite suspension permanent. And as the world’s greatest athlete continue to garner headlines and public acclaim with his every move, resentment from the AOC’s Brundage, Ferris, and other leaders in the AAU festered.

There were no Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) contracts in the 1930s. Owens sought ways to lift the suspension and compete. Then – as now – track meet sponsors would pay appearance fees to top amateur athletes, and it was something the AAU allowed. But it would not do so for Owens.

When the New York Caledonian Club made an appearance fee offer, extending an invitation for Owens to compete in a meet on September 17 at Yankee Stadium. Owens accepted. But one thing stood in the way: the AAU sanctioned the Caledonian Club meet. In response, the AAU refused to allow Owens to enter and threatened to withdraw amateur status for any other athlete who completed at the meet.

Having no choice, the Caledonian Club canceled its event. This was the first of several salvos which the AAU and/or the AOC would launch towards Owens over the next few years, effectively depriving him of the opportunity to ever run competitively again. At age 23, his track and field career was over.

Still, Owens longed to run. Cuba’s athletic association signed a contract with Owens to have the Buckeye Bullet compete against Conrado Rodrigues, its top sprinter, in Havana. When Brundage caught wind of it, he threatened to ban Rodrigues from all amateur races in the U.S. if he ran against the ‘professional Owens.’ Rodrigues had to withdraw, and Cuba’s athletic association – still wanting to fulfill its contract and keep Owens coming there – recommended substituting Julio McGrew. A reluctant Owens accepted.

SURVIVOR MODE

On a cold, wet track the day after Christmas, Owens was given a 40-yard head start. He ran 100 yards in 9.9 seconds, just nipping an accelerating Julio McGrew at the tape. It was an ignominious end to what was otherwise a landmark year for Owens.

Sadly, it was also the first of countless times Owens would race against horses, dogs, and other animals to make a living. His track and field career and his dignity – best destiny and true calling – had been stripped away from him. Brundage was president of the U.S. Olympic Committee for decades, and later became president of the International Olympic Committee. But over the years, due to his continuous unjust treatment of Owens and other Black athletes, such as Tommie Smith and John Carlos in 1968, he earned the derogatory nickname of “Slavery Avery.”

As the Olympic Games receded, so did Owens’ income-earning opportunities. Jobs dried up. In 1938, Owens launched a dry-cleaning business in Cleveland. It failed. In May 1939, Owens filed for bankruptcy. It would take the Cold War to help revive the Buckeye Bullet’s dignity and reputation.

PARTS OF THIS ARE EXCERPTS FROM CHAPTER 10 OF “Jesse Owens: Sensation, Superstar, Survivor, Symbol,” being scheduled for publication later in 2026 by Kent State University Press

SOME SOURCES USED

Chicago Defender, August 22 and August 29, 1936

New York Times, August 19, 1936

Baker, William “Jesse Owens: An American Life,” pages 111-112.

Larry Snyder “My Boy Jesse” Saturday Evening Post November 7, 1937, p. 97

New York Times, August 18, 1936

McRae, Donald “Heroes Without a Country,” p. 165, and Baker, p. 115

New York Times, August 18, 1936

New York Times, August 17, 1936

Chicago Tribune, August 20, 1936

Cleveland Call and Post, August 20, 1936

New York Amsterdam News, August 22, 1936,

F. Erik Brooks and Kevin M. Jones, “Jesse Owens: A Life in American History,” p. 93

Clowser, Jack, “Doors Swing Open for Jesse” Cleveland Press, January 26, 1966

Moro, Barbara 1961 interview with Owens

New York Times, August 30, 1936.

Lantern Oasis, a student publication of the Ohio State University, May 1, 1986, p. 7

McRae, Donald “How did it come to this?” The Guardian, Observer Sport Monthly, September 3, 2000

Special thanks to the Jesse Owens Collection Guide, the Ohio State University’s University Archives

Special thanks to my colleague and trivia GOAT Dr. Clarence Johnson for his assistance

Some past Jesse Owens stories and features appearing in eyeoncleveland.com include: