By JOHN KEREZY, eyeoncleveland.com founder

CUYAHOGA FALLS, MARCH 26, 2024 – A student athlete in a New Jersey high school state semifinal game scored what should have been the winning basket in the last second, according to game video. Yet referees ruled the shot was made after time expired. In Ohio, a scorebook error in a OHSAA Division I regional final allowed a basketball player with five fouls to re-enter a game. His team won, due in part to points he scored after committing what should have been his disqualifying foul.

Seems nowadays we value winning above everything else. That is what makes what Jesse Owens did on March 28, 1936, at a track meet at Cleveland’s Public Hall, all the more remarkable.

Owens, a sophomore at Ohio State known as the Buckeye Bullet, was not invincible as a sprinter. In fact, at that time many track observers felt the fastest human in the U.S. was Eulace Peacock, a sprinter from Pennsylvania’s Temple University. Nearly a year younger than Owens. Peacock had beaten Owens the last three times the two had competed against each other. Newspaper reporters heralded the duo’s competitions. Some observers felt that Peacock was the odds-on favorite to be the top sprinter for Team USA at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.

RIVALS BECOMING FRIENDS

Peacock and Owens first opposed each other on the track in the Spring of 1935. Owens held the upper hand in these encounters. After Owens broke three world records and tied a fourth at the Big Ten track championships in May, an enormous media spotlight shined on him. With that attention came increasing amounts of pressure focused on his every move.

Owens and Peacock had contrasting running styles. Decent to very good at the start, Owens would move swiftly and effortlessly – so it seemed – with excellent form through his sprint. Writers compared his stride to a deer or antelope. Peacock, who played football as well for a time, started slowly but would accelerate continuously as he raced down the track. He would frequently come barreling from behind to take the lead in the last 5 to 10 yards of a sprint. That’s how he earned a nickname: the Midnight Express.

At 5 foot 10, 165 pounds, the Buckeye Bullet was about 15 pounds lighter than Peacock, who was slightly less than 6 feet tall, when the two competed in 1935. A year later, both were not in the best of condition for that March meet. Owens had been academically ineligible due to grades, and he wasn’t able to practice with his teammates. Peacock, recovering from an injury sustained in Italy in the fall of 1935, was overweight.

As they faced each other and other top sprinters in 100-yard dash finals in 1935 in California, Nebraska, Canada, New York, and elsewhere, Peacock and Owens came to know each other well. They had became friends, and when Peacock came to Cleveland in March he was seen socializing in the East 105th Street neighborhood with Owens’s sister and other Owens friends and family members. At the time Owens lived with his family on East 100th Street, in a home the City of Cleveland is now moving to designate as an historical landmark.

THE SPORT

In the mid-1930s, track was one of the top spectator and participant sports in America. Pro basketball didn’t exist, and pro football was in its infancy. Young boys and girls who couldn’t afford a basketball hoop, baseball bat or gloves could always run, and they did. College football would bring the biggest crowds to its games, but college track was also an attraction. Two major events every spring draw huge crowds today, just as they did 80 years ago. About 10,000 to 15,000 fans would take in the Drake Relays in Iowa every April. Franklin Field in Philadelphia would routinely attract 15,000 to 20,000 fans at its famous Penn Relay each spring. There were 40,000 fans in Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum to watch the University of Southern California’s track team oppose Owens and Ohio State there in June 1935.

A throng of 15,000 journeyed to Lincoln, Nebraska, to watch the National Amateur Athletic Union Track and Field Championships there in early July 1935. Owens, Marquette’s Ralph Metcalfe and Peacock were the top sprinters there, and Owens was expected to leave the competition with at least two first-place crowns. But it didn’t happen. Peacock exceeded 26 feet for the first time ever in the long jump, and bested Owens — 26 feet, 3 inches to 26 feet, 2 ¼ inches – in the field event. It was the first time ever in track that two athletes leaped beyond 26 feet in a meet.

In the 100-meter final, the Midnight Express finished first in what would have been a world record of 10.2 second, save that the time was disallowed due to tailwinds. Owens placed third, behind Peacock and Metcalfe. It was the worst finish of Owens’s collegiate career.

“This was to have been Owens’s show,” wrote the New York Times’ sports reporter Arthur Daley, “…and Peacock took the play right away from him.” “Peacock, like Owens, is only a sophomore and has his best years ahead of him. He is physically stronger than Jesse,” added Braven Dyer, sportswriter for the Los Angeles Times.

THE CLEVELAND RACE

Cleveland was the fifth-largest city in the U.S. when Jesse Owens first came to acclaim in track and field. It was a hub for all types of sports activity, and the opening of its cavernous Municipal Stadium contributed to this. Olympians from across Europe who left Los Angeles after the 1932 Summer Olympics there stopped in Cleveland for a track exhibition.

Like many other meets at the time, the 1936 event featured a section for high school athletes, and a set of collegiate track events. It was a precursor to what became known as the Knights of Columbus track meet, an annual sports event which attracted top national and international track and field athletes to Cleveland, between 1941 and 1993.

Newspaper reports stated that nearly 6,000 attendees came to Public Hall to watch the track meet that March night. The main attraction that night was the showdown between Owens and Peacock. The Associated Press sent one of its top sports editors, Alan Gould, to Cleveland to report on the results.

But something unanticipated happened when Owens, Peacock, and two other athletes faced off in the finals of the 50-yard dash. The track surface was wood, not cinders. Race officials used starting blocks, since the runners couldn’t dig holes to plant their spikes at the starting line.

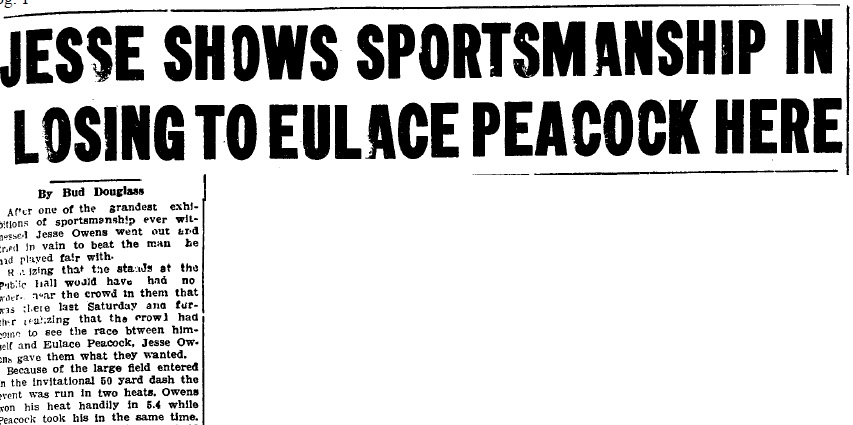

Owens exploded at the starting gun and won the final handily in a time of 50.5 seconds. When he looked back, he saw Peacock at the other end of the track. One of Peacock’s starting blocks slipped, and he almost fell to the floor. He didn’t even attempt to complete the dash.

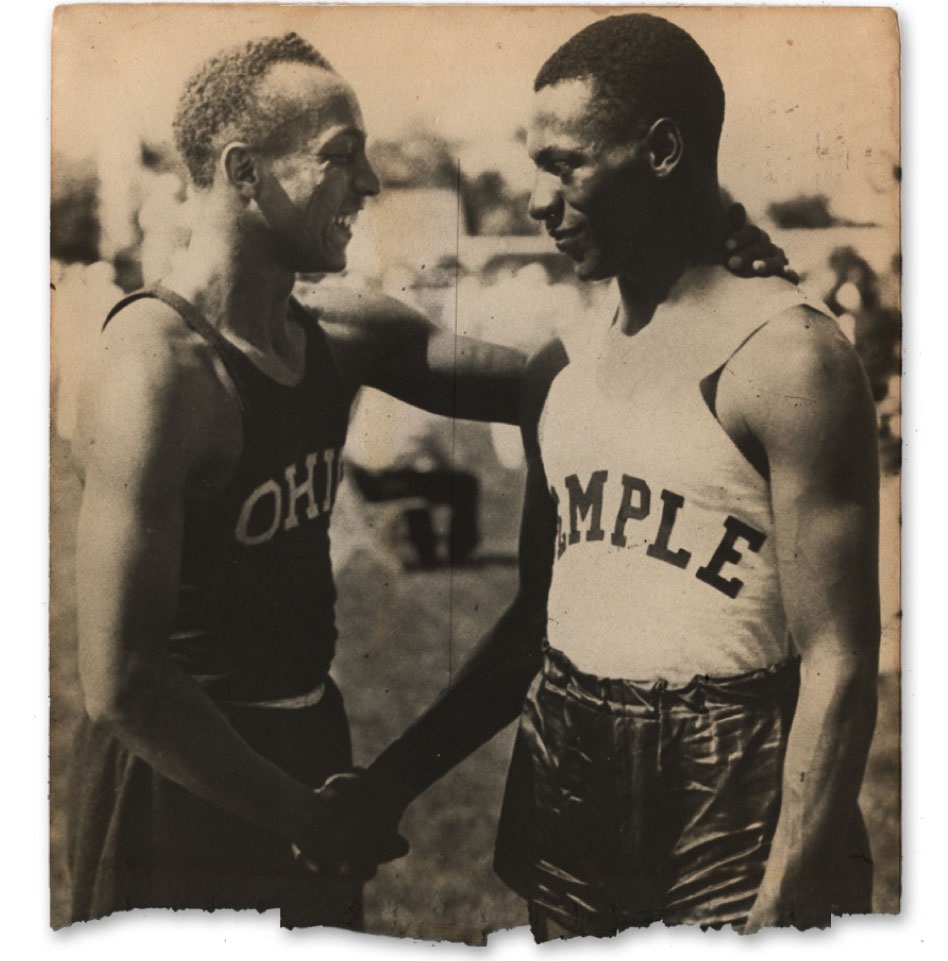

Owens immediately went back to Peacock. He put one arm about him in consolation, and the two walked together over to the meet officials. Owens began pleading with them, insisting that they re-run the 50-yard dash final again. He knew the fans came to watch a Peacock-Owens showdown, and in the interest of good sportsmanship he wanted that to happen. Although he had won ‘fair and square,’ the Buckeye Bullet felt it in the best interest of the meet for he and the Midnight Express to battle it out.

Owens’s persuasion succeeded. After an interval, officials re-ran the 50-yard dash final. This time Owens also insisted that he and Peacock change lanes. He didn’t want another starting block malfunction to detract from the race. All four finalists got off to a clean start in the re-run, and at the finish Peacock nipped Owens by just one foot. The official time for both athletes was 50.4 seconds.

The Associated Press dutifully reported on Peacock’s triumph over Owens. But reporters in Cleveland saw the bigger picture. “His (Owens’s) exhibition of sportsmanship won him more admirers than he would have if he won the race,” wrote Bud Douglass in the April 2, 1936, Cleveland Call & Post.

Among its commentary on national and international problems, the Cleveland Plain Dealer devoted an editorial to what Owens did in its March 30 paper. Headlined “Owens’ Sportsmanship,” it began like this: “Jesse Owens has won many honors for his outstanding ability to get there first. He rates similar recognition for fine sportsmanship by his action Saturday night in insisting that his rival, Eulace Peacock, be permitted two chances in the 50-yard dash at the Public Hall track meet…” The last sentence read, “This colored youth from Cleveland’s East End rates a salute from all who honor fine sportsmanship.” (NOTE: Sadly, such racial connotations were common in this era of journalism in the U.S.)

The Public Hall triumph marked the fourth consecutive time Peacock had bested Owens in a race, but the Temple star didn’t see it that way. Peacock penned a brief letter to meet officials that night, declining to accept first place. “Jesse, one of the finest sportsmen I have ever met, is entitled to the medal more than I,” he wrote.

SAD AFTERMATH

The race in Cleveland was also the last time Peacock beat Owens. The Midnight Express suffered a severe tear of his right hamstring at the Penn Relays the following month. He was in the hospital when the Relays ran its 100-meter final, which Owens easily won. Try as he might, Peacock couldn’t overcome his injury and finished out of the top three places at the 1936 U.S. Olympic Track and Field qualifying trials later that year. Owens sailed to Germany and to fame for his performances at the Summer Olympics in Berlin. There he won four gold medals and forever squashed the myth of Aryan supremacy as an unhappy Adolph Hitler looked on.

His sprint dominance over, Peacock recovered sufficiently to place third in the long jump at the 1937 NCAA Track and Field Championships. He and Owens remained life-long friends, no doubt due in part to Owens’s sportsman-like gesture in Cleveland.

QUESTIONS FOR CONSIDERATION

FOR COACHES: How do you instill fair play and good sportsmanship in your student athletes? Are there ways you can encourage excellent behavior from them? How might Jesse Owens’s story be used as an example?

FOR EVERYONE: Have you ever needed a “re-run” or a do over? If so, what’s stopping you from asking for one now?

Kerezy is an associate professor of Media & Journalism Studies at Cuyahoga Community College. His second book, a biography of Jesse Owens, is undergoing peer review at Kent State University Press for publication in 2025.

SOURCES & MORE

Anyone interested in knowing more about the rivalry between Owens and Peacock should read Michael McKnight’s terrific 2016 account “Faster than Fastest” on Sports Illustrated‘s website. The link is https://www.si.com/longform/peacock/index.html

Matt Goul, Cleveland Plain Dealer and Cleveland.com reporter, https://www.cleveland.com/highschoolsports/2024/03/ohsaa-responds-to-garfield-heights-toledo-whitmer-foul-discrepancy-in-boys-basketball-regional-final.html

Cleveland Call & Post, March 26, 1936, and April 2, 1936

Michael McKnight, “Faster than the Fastest” from Sports Illustrated Long Form, found at https://www.si.com/longform/peacock/index.html

Some Associated Press stories of the meet are embedded in this story

Washington University (St. Louis) interview with Eulace Peacock,

http://repository.wustl.edu/concern/videos/gm80hz989

Case Western Reserve University encyclopedia of Cleveland history, https://case.edu/ech/articles/t/track-and-field-sports#:~:text=Beginning%20in%201941%2C%20the%20annual,sponsorship%20became%20difficult%20to%20obtain.

The Plain Dealer editorial appeared on March 30, 1936. The Cleveland Call & Post story appeared on Page 1 of the publication three days later, on April 2, 1936.

Some details also come from Jeremy Schaap’s book “Triumph” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing, 2007) and William Baker’s “Jesse Owens: An American Life” (University of Illinois, originally published in 1986).

MANY THANKS TO librarians at Cuyahoga Community College, the Cleveland Public Library and to Elizabeth Piwkrowski at Cleveland State University’s Michael Schwartz Library and the Cleveland Memory Project for their assistance.

Follow-up: Contact Kerezy at john.kerezy@tri-c.edu or at 216-987-5040

Outstanding, insightful and timelessly relevant piece, Professor Kerezy! Thank you for teaching and sharing.

LikeLike

Thank you kind sir!

LikeLike